Following in the tradition of previous game projects such as Uncle Roy All Around You and Day Of The Figurines, You Get Me uses a game structure and then stretches it and extends it. It explores whether a game can be a conversation and whether technology bridges or reinforces social divides. Online players – all using terminals at the Royal Opera House – choose one of eight young people in Mile End Park and develop a conversation with them.

A description of the work

The development of the work was supported by Caitlin Newton Broad who visited a huge range of community groups, colleges and arts organisations in the East End to invite young people to a series of workshops at the Urban Adventure Base over the summer of 2008. Eight people were chosen to work on the project: Jack Abrahams, Hussain Ali, Tendai Chiura, Ivan Neeladoo, Fern Reay, Rita Ribas, Rachel Scurry and Jade Laurelle Stevens.

Matt, Ju and Nick worked with them to create personal geographies. Each of the eight explored important places or events in their life and formed them into a map; some were tight logical areas (Rita’s was arranged around the swimming pool in which she had nearly drowned) while others were more freeform (Hussain linked his home with key places in Bangladesh). And from these maps a critical question about their lives were brought to the surface. These questions came to be the animating force of the work.

Visitors to the Opera House play on the internet. The front page reads,

“Welcome to You Get Me.

This is a game where you decide how far to go. At this moment a group of teenagers are in Mile End Park. Each one has a question they want you to answer.

Pick a person and their question. Choose carefully because you only get one shot at this. And the others you didn’t choose will then try their best to knock you out.

Here they come..”

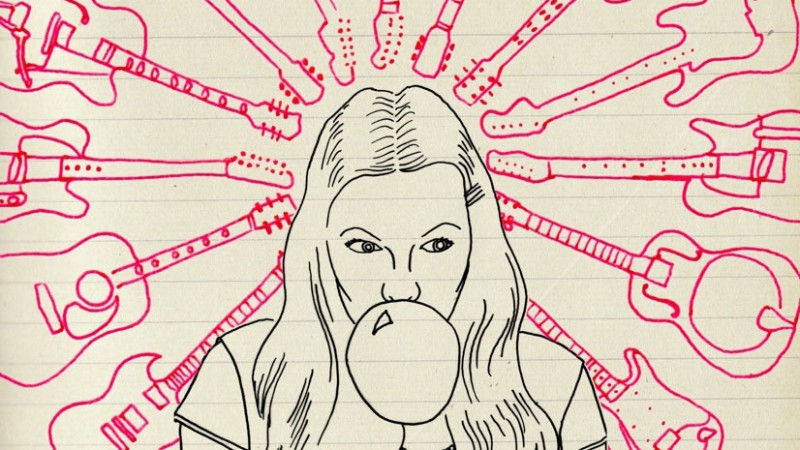

Visitors choose from one of the teenagers (known as runners) based on a picture of them and their question. Rachel asks “What is your line between flirting and cheating?”, Jack wants to know, “Would you employ me?”. You hear a story from that person (Jack describes jumping the barriers to Southend and pissing in a cup on the back of the rail replacement bus) and are dropped into the game.

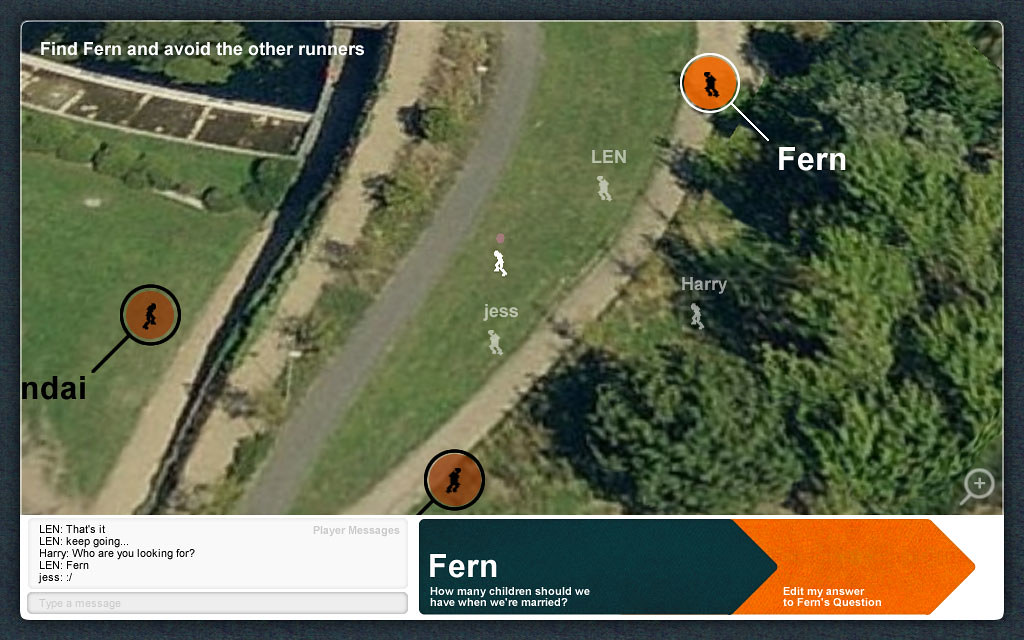

By navigating your avatar through a virtual Mile End Park you can find your chosen runner while avoiding the others: if one of the others get too close you are knocked out of the game.

In this first stage your goal is to listen to the personal geography of your runner over the walkie talkie stream. As you learn more about them their question begins to deepen and make more sense. You then track them down and type them an answer to their question. If they don’t like it, they throw you back: you need to listen to more of their personal geography and come up with a better answer.

If they feel that your answer is intriguing the runner invites you for a private chat. They switch to the privacy of a mobile phone and call you; in turn you can type them messages. A night time photo of the park slowly zooms to reveal the person you are talking to as a pixellated presence on a distant pathway.

This one to one exchange allows them to get your direct input into their life. They have framed the most important question in their life at that moment and they want your opinion. Hussain, for example, is wrestling with leaving home and asks you how you did it: does it get easier over time? Are all parents so obstructive and incomprehending?

Once you have finished your conversation they take a picture for you. The last thing you hear might be “This is Fern. It’s 3.45 in the afternoon on Friday 12th September. I’m near the canal with the Pallant Estate behind me and I’m taking a photo for you. You get me.” As you leave the Royal Opera House the photo arrives on your phone.

The work extends Blast Theory’s focus on the social impacts of mobile communications technologies. Whereas previous works such as I Like Frank and Day Of The Figurines bring groups of strangers into spaces that are both social and ludic as equal participants, You Get Me makes eight individuals the agents of the work. It makes listening, learning and understanding the core mechanics of a game.

The piece comments on the disparity between the culture of the Opera House and the wider London community in which it is situated; it bridges the existing divide while emphasising the limitations of attempts to do so using technology or culture.

You Get Me was commissioned for Deloitte Ignite, a weekend festival at the Royal Opera House from 12-14th September 2008, curated by choreographer Wayne McGregor. It was developed with the support of the Mixed Reality Lab of the University of Nottingham with additional support from Urban Adventure Base, Chisenhale Gallery Education Program, Fundamental Architectural Inclusion and Mile End Park (Tower Hamlets Borough Council)