Our first project using mobile devices with audiences was Uncle Roy All Around You in 2003. At the time, it was a novelty to record audio or navigate maps using a touch screen. We had to choose a word to refer to the device that we give you at Front of House (a PDA – ‘personal digital assistant’ – and stylus, with a modem). It prompted a discussion about whether it was better to call it a “device”, a “PDA” or something else?

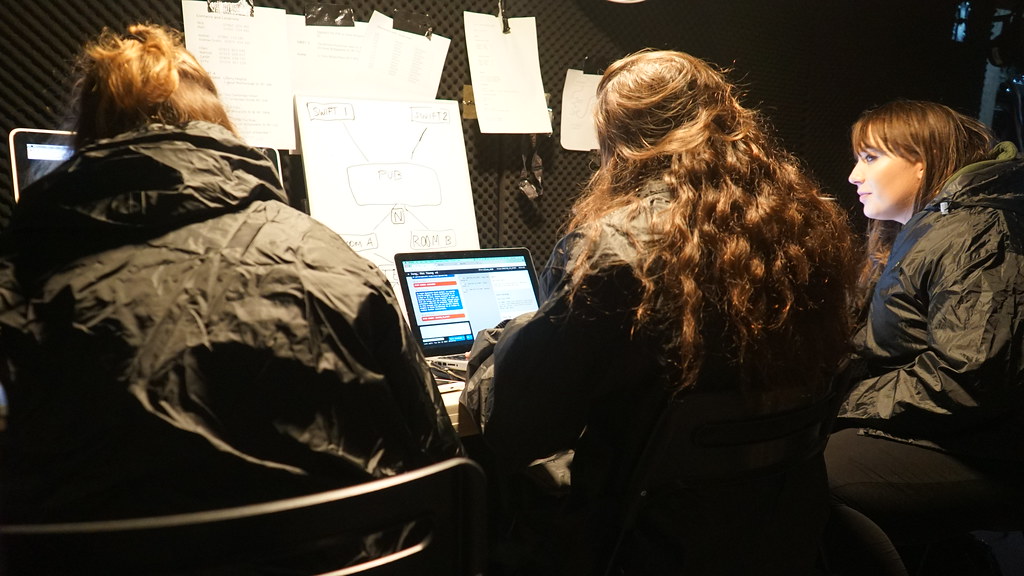

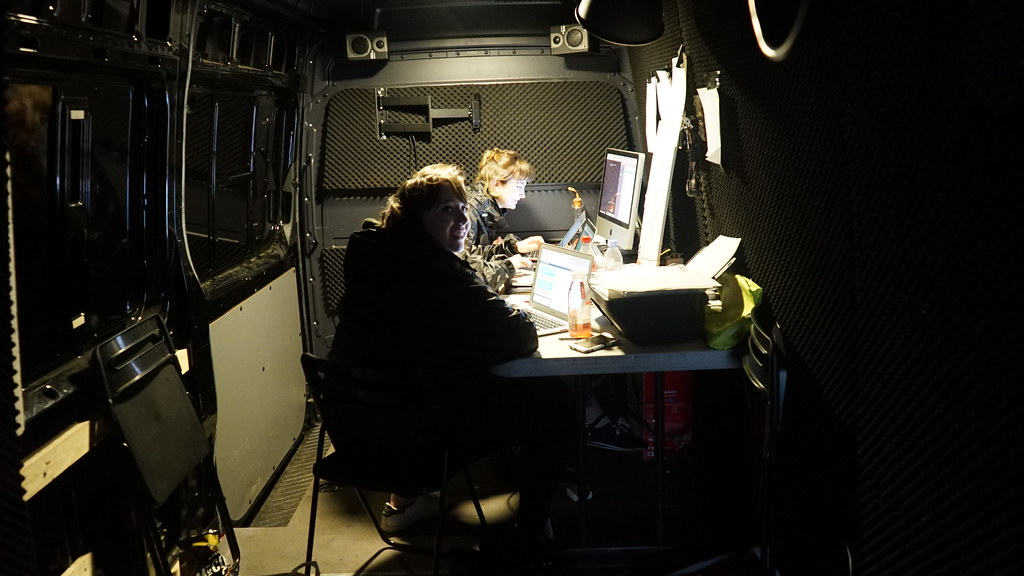

Front of House often has to do several things, depending on the project. As with Uncle Roy All Around You, it might need to explain how to use some novel technology. It may also need to set out terms and conditions, or to brief you on taking part safely. However, in all cases it’s the threshold for entering the world of the work. It sets expectations and the trajectory for how you participate. So, here’s three questions we keep in mind…

1. Can we make it part of the work?

We often look for a form that serves the practical needs of introducing you to what you’re about to do while blending with the world of the work itself; blurring the threshold between you as a person and you as a participant. Or, as Ju puts it, trying to avoid ‘narrative drop’.

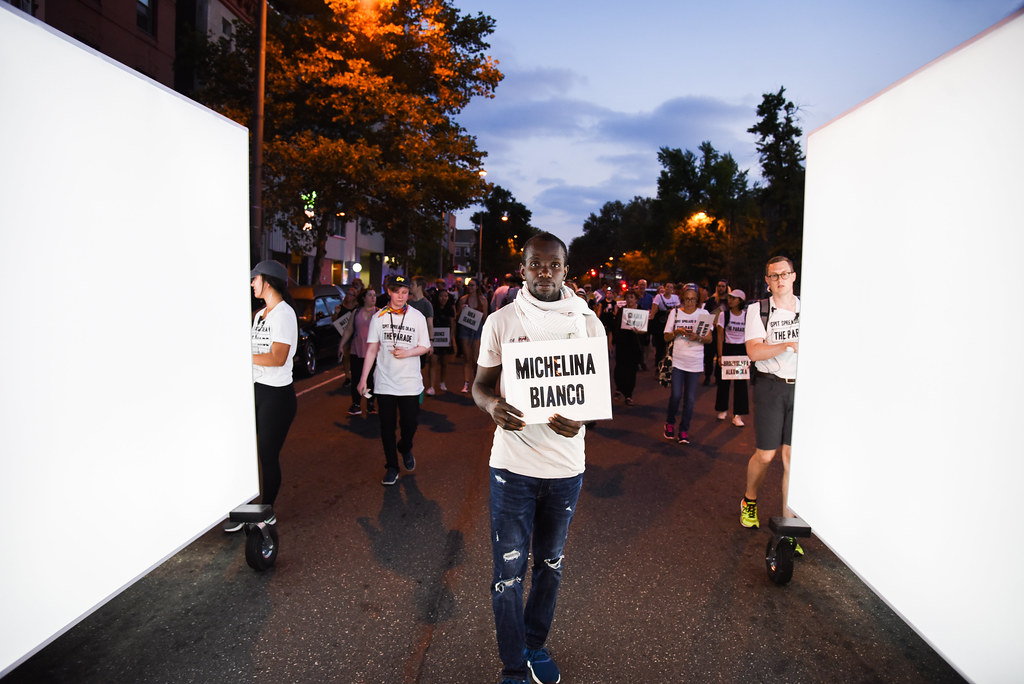

For different projects, Blast Theory’s Front of House has included a mobile web app where you choose someone to commemorate on a parade; an abandoned shop where you’re briefed on a surveillance operation; and an automated phone call on a street corner.

2. How do we avoid geeking out?

For Uncle Roy All Around You, we were lucky enough to work with artist Sheila Ghelani. She came up with a solution for how we named the device at Front of House: not to name it anything at all. Instead, Sheila slides the PDA across a counter towards you, with the phrase “you’ll be using one of these…”.

People rarely come to our work to geek out over technology: so we try to focus on what you need to do, instead of the devices or the hardware.

3. Does it work?

We try to treat every word at Front of House (and how it’s said) with as much care as the scripts within the work itself – but changes in context or audience can throw things off. Fifteen years into touring Rider Spoke and we still have discussions at each gig about how we describe the work to a particular audience, and when is the best point to offer large type to audience members struggling to find their reading glasses.

Get news like this straight to your inbox

By signing up to our mailing list you’ll receive monthly emails about our upcoming projects, news, competitions and more. Here’s how we use your data and how you can opt-out.